Népal the first time: Round Two, the Passes…

Par Craig Calonica

Winter of 1981/82

Moving fast and efficiently was extremely important, we only had enough food and cooking gas for 6 days to get over the passes, taking longer than 6 days wouldn’t have ended well, we had to get over the passes in that time frame or we were toast.

After we finished our climb on Pumori, we walked down to Namche Bazaar (the Sherpa capital of the world) to rest and prepare for our next expedition, which was to go over three 20,000 ft passes in winter from the Everest region to Makalu Base Camp.

This had never been done in the winter before, if successful it would make it another first for us in Nepal’s winter climbing season and another first in the Nepalese history books.

Jim and Steve had to return to the US, which shaved our group down to three Ned, Jan and myself. In the end, it was to our benefit us as we could cover ground much faster with a smaller group. It also meant we would get up the passes much faster as two of the passes required slow technical climbing and going over with three was definitely much faster than a group of five and time was critical for a trip like this.

Saying a mistake wasn’t allowed is putting it lightly, it meant death and we were very well aware of that fact.

As before, the Sherpa’s could only go to Base Camp, from there we were on our own, which I personally preferred as it’s what I was used too… I didn’t know any other way. It also kept our team small which, as mentioned, is faster, much faster. As with the climb on Pumori, we had no form of communications with the outside world, we were on our own, if anything went wrong we would probably never be found as the area is vast and unmarked. Due to that fact, it was much more committing than the climb on Pumori, as at least our Sherpa’s were at Base Camp and they could run to Lukla for help if the need came up, but that wasn’t the case here, we were on our own out in the middle of nowhere, which meant there was no room for mistakes. One single mistake here and that’d be it… no one was going to come looking for us, not where we were, it was off limits to the Sherpa’s in the winter and there were no foreign climbers in the country at the time that could go searching for us, no helicopter rescue services, nothing, we were on our own and fully committed, saying a mistake wasn’t allowed is putting it lightly, it meant death and we were very well aware of that fact. At best they might organize a search group in May, but all they would find, if they found anything, would have been frozen bodies, which was a grim prospect.

Moving fast and efficiently was extremely important, we only had enough food and cooking gas for 6 days to get over the passes, taking longer than 6 days wouldn’t have ended well, we had to get over the passes in that time frame or we were toast.

Since we had never been over these passes or in this area before, we really didn’t know what we were up for nor how long it would take, our Sherpa’s suggested a time frame and so that’s what we went with. While we were making our way over the passes our Sherpa’s were to fly to the Tumlingtar airport, get some porters to carry supplies and walk to Makalu Base Camp where we were to meet up at. On paper it looked good, but as we all know, shit happens and this would end up being one of those times when that’s exactly what happened.

The passes…

The first pass is called Mingbo La, it’s next to Ama Dablam and approx 5 miles from Everest base camp. The Sherpas came to Base Camp with us and pointed out the first pass, which was this steep wind fluted ice face… It looked intimidating and dangerous. Just when we got to base camp, we noticed a body buried under a pile of rocks, apparently a team of climbers tried to go over the pass a few months earlier and a Sherpa on the team took a climbing fall going up the pass and died. Why they didn’t carry him out is beyond me, but they didn’t and it completely freaked out our Sherpa’s, making matters worse, they knew him and his family, we could see that it made them extremely uncomfortable and it was clear they didn’t want to spend the night at base camp as planned, and so we sent them on their way.

We got up early the next morning and started to make our way to the first pass. Since I was the stronger climber, I lead all the technical climbing sections of the passes. The first pass had several short vertical sections of ice we had to navigate to get onto the glacier, I made my way through the section quickly and belayed Jan and Ned through the sections in good time. We got to the base of the first pass which was this steep 80 degree ice face and approximately 1,200 vertical ft. We had one ice axe each, one 60 m 9 mm climbing rope, a few ice screws, one piton, a few carabiners, some webbing and that was it. We were also lugging our packs which weighed around 65 pounds each, climbing on these steep faces with these heavy bulky packs was not easy nor desirable but to make good time, we had no choice but to climb with them and we did. To save time, Ned decided to climb behind me, he tied into the rope about 30 ft. behind me and moved in sync with me. I was not comfortable with it because if he fell or I fell, we’d both go flying away, and there would be no way for Jan to stop the two of us if we were to fall. Still, I was climbing well and was strong and felt that even if Ned fell, I’d have a good enough stance to stop it, as long as he didn’t leave a lot of slack between the two of us.

All was going well and we were moving up the face fast. I didn’t put any ice screws in and was just climbing up the face at a pace which made it hard for Ned to keep up. When I got to the top of the pass I came upon an overhanging cornice, I couldn’t go around it or climb over it, the only option was to chop a hole through the cornice with my ice axe, which wasn’t easy as it had to be big enough to go though and it was almost vertical, I only had one ice axe and so my only contact were the front points of my crampons while I hacked away at the cornice with my ice axe… It seemed to last forever, my calves were on fire and I was starting to get pumped from hacking away at this giant ice cornice at 20,000 ft. Finally I managed to chop out a hole big enough to get through, as I started to move up into the hole, my pack got caught on the edge of the hole and I almost went flying off backwards, I stuck my ice axe in last second and stopped myself from falling, which surely would have been the end for all three of us… as we all would have gone flying down the entire face. Luckily that didn’t happen, but I still get the chills thinking about it to this day.

Shortly afterwards, Ned and Jan were with me on the top of the pass and we began walking down to the end of the glacier where we decided to spend the night at. It was late in the day and we had to move fast to take advantage of the last light. I made it down about 40 minutes before Ned and Jan and set up the tent and started brewing up some tea… in time, they showed up, I gave them some tea, had a quick bite to eat and passed out shortly afterwards. The Sherpa’s said it would probably take us two days to get over the first pass, we got up and over it and down to the end of the glacier where we camped at in around 7 hours. The good news is we were ahead of schedule, even though we took a risk to climb like that, it bought us some time.

We got up early the next morning and began to move onwards to the second pass called the West Col pass. It was at this time that we realized we had a slight problem, we couldn’t tell which of the 30 faces were the pass, all of them looked like they could have been the pass, but there was only one and it was important we choose the right one or we’d be screwed…

All we had to go by was a map, we had no pictures of the pass nor description. We decided this one face must be the pass and started walking towards it, suddenly we realized we were losing elevation when we should have been gaining elevation and so we turned around and started heading towards our next choice…

Frozen lakes

The area was this vast open area with five frozen lakes, which we walked across to save time, every now and then they’d shift and make these loud cracking sounds, like the ice on the lakes were caving in, at first it made the hair in my head stand out straight, but after awhile, I got used to it, but I did pick up the pace some when I was walking across the lakes.

After several hours of walking and crossing these frozen lakes we got close enough to this face we thought might be the pass, with the help of some binoculars we saw a piece of red climbing webbing someone left on the face via a previous climb, we were filled with relief as we knew we were OK… it took an entire day to get to the base of the pass and so we decided to camp there for the night and go over the pass early the next morning.

We started out early and this time I led the pitches without Ned being tied in short behind me as the climbing was more technical, nor was it straight forward, there were several tricky traverses and climbing moves that took time to work out. That said, we made it up and over quickly without any issues.

From the top of the pass we walked onto a giant glacier that continued all the way to the next pass, Sherpani Col. We decided to set up camp just before the pass so we could have a full day to get over the pass and down to Makalu Base Camp.

Sherpani col

We started out early the next morning for Sherpani Col, there was no climbing involved with this crossing, it just dropped off the edge of this giant glacier. Finding the spot to go over was the crux of the pass as there wasn’t a clear notch indicating an exit or pass. The first spot we tried was a 5,000 ft ice cliff and rock wall… it definitely wasn’t the exit point, it was also extremely windy. The only way to look over the edge was to lay down on my belly and crawl over to the edge to see what was below. After several attempts to find the exit point, I finally found a way to get off the glacier and begin the descent down to Makalu Base Camp, which wound up being the crux of the pass. We had to rappel off the glacier and down this steep ice and rock face. We finally got to a point where we no longer needed to rappel but the going was dangerous and slow as we were now on a steep rock slab with patches of ice, unstable rock and covered with sand on top of the rock slab which make you constantly slip, it was sketchy to say the least.

After that section we ran into a giant boulder field, some were the size of box cars, many were unstable and moved when you stepped on them, if any of them shifted at the wrong time, they’d squash you like a bug, moving quickly over these boulders was important as the more time you spent on them the boulder would shift or rock which in turn could cause it to roll over, which wouldn’t have ended well. I had been going through boulder fields like this since my childhood days, I knew how to navigate them well and I flew through them with ease, Ned and Jan on the other hand had difficulties, they were not comfortable on this terrain and moved slowly, which was the wrong thing to do, but they managed and got though the boulder field without any issues.

From there we were on easier ground and we hurried down to the bottom of the pass to find our trusty Sherpa’s who were supposed to be there waiting for us. We spent the next four hours walking through this narrow valley and passed several base camps, but no Sherpa’s… We finally stumbled onto the base camp of a French solo climber trying to climb Makalu. We asked him if he had seen our Sherpa’s but he hadn’t, if they made it there they would have passed his camp onto the camp we planning to meet them at.

It became clear that our Sherpa’s didn’t make it yet and so we were faced with a major decision.

Wait and hope they make it, or we move on and hope we run into them on the way out. The French climber was almost out of food and didn’t have anything to spare. We on the other hand had about one day of food left and two canisters of gas for heating water and cooking. We didn’t dare stress the French climber nor his supplies so we decided to carry on and try to find our way out with the hope of meeting our Sherpa’s in the process. It was at this time that Ned announced he left the map for the way out from Makalu Base Camp with the Sherpa’s which meant we were screwed as we didn’t have anything to go by.

The French climber told us to follow the river down the canyon until we came upon a frozen river going up a hill on the right side of the canyon. It would be here we would find a trail which eventually would lead us to a pass and then a village far down in the valley below. He said it was about a weeks walk to the first village, which meant if we didn’t run into our Sherpa’s on the way out, we were pretty much screwed as we’d be running on empty, but at least we had water which is essential, as you can go days without food if you have water.

The blizzard

We spent one night at the Makalu Base Camp and took off early the next morning not knowing what laid ahead. Right when we took off it begin to snow, it eventually turned into a full on blizzard and dropped about 4 ft of snow, which made the going slow. The trail down the canyon was basically non existent, every now and then I’d see something that resembled a path or a mark on a tree someone made for reference, Ned and Jan were wiped out and so I’d run ahead trying to find a sign of a path much of the time in knee to waist deep snow. I’d find something that seemed to be a trail or marking and I’d run back and bring them to that point and continue. We spent several days doing this and it was taking a toll on Ned and Jan, both were wiped out, we had no food for days and were reusing tea bags to have something hot to drink as we still had some gas.

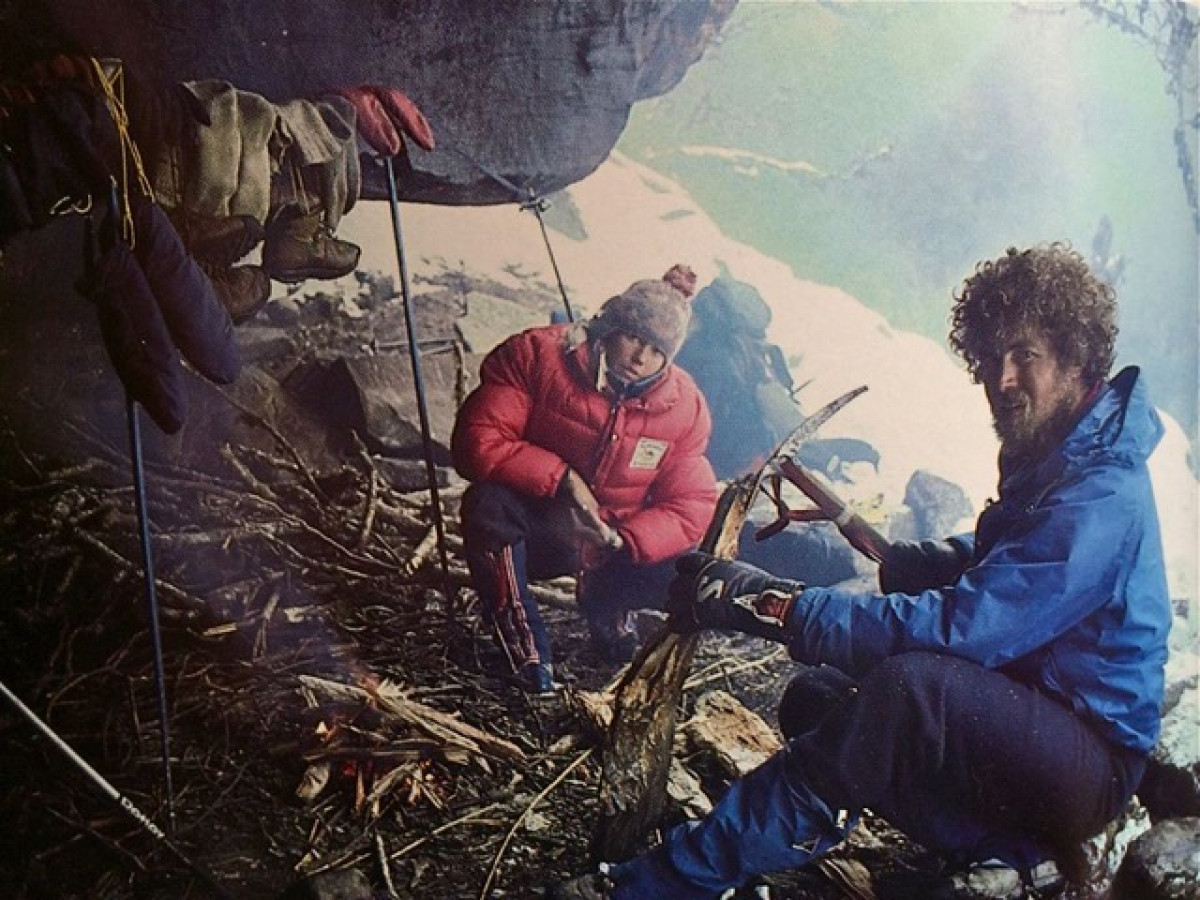

After the 5th day, we came along the frozen river, the French climber told us about, or at least we hoped this was the river he was talking about. We found a cave a little above the canyon and made a fire and for the first time in days and tried to dry out our socks, gloves and shoes. That evening I went scouting around and found a trail, which indicated we were in the place the French climber told us about. The next morning we began the long trudge to get over the pass, Jan collapsed about 2 hours from the top of the pass, Ned didn’t want to continue on as he didn’t want to push Jan. Not wanting to stop, I offered to carry Jan’s pack after giving her a rest, both agreed to this and after Jan felt better we continued with me carrying Jan’s pack. I ran ahead in hope to get to the top of the pass and hopefully see a village in the valley below which would boost both Ned and Jan’s morale. Unfortunately that would not be the case, I got to the top of the pass only to see a frozen lake down below and no valley or village.

There was a long slope going up from the lake that led to a ridge. The slope to the ridge was buried in deep snow, and while it was a major blow to our moral and spirit, I was sure we’d see the valley below from the top of that ridge. Ned and Jan wanted to stay at the lake that night and I wanted to carry on. A big storm was coming in and I didn’t want to be stuck at the lake in a blizzard, it’d pretty much be the end, as we’d probably get trapped there if not buried in an avalanche as we were surrounded by a bunch of avalanche prone slopes. After making my point, Jan and Ned decided to go along with my plan to walk up to the ridge… The snow was really deep in places, sometimes up to my waist, making the going slow, to make it as easy as possible for Ned and Jan I broke trail the entire way up carrying Jan’s pack on top of it. Finally after many hours of struggling up this face in deep snow, I made it to the ridge… I took off my pack and ran over to the edge hoping there would be a deep valley and village on the backside of the ridge and sure enough there it was, a deep, deep valley and a small village with smoke coming out of a hut, right then and there I knew we made it.

I called down to Ned and Jan who were still coming up to the ridge to give them the boost, tired as they were the news gave them a well needed boost of energy and they picked up their pace and were beside me in no time. The sense of relief was immense and overwhelming, we had been walking non stop for 6 days lost in the middle of the Himalaya without food, it’s safe to say we were near the end of our rope. Darkness would be on us soon and so we set up our tent crawled in and collapsed into a deep sleep, except this time, it was different, we knew we made it, it was one of the deepest sleeps I’ve ever had…

The sherpa's arrived, finally some food!

We woke up in the morning and we’re about to heat up some water and make some tea with out several day old tea bag when we heard some voices… suddenly with no warning, someone unzipped our tent door, slightly shocked we jumped back, right then one of our Sherpa’s stuck his head into our tent with a big smile… It was completely unexpected, but it was great to see these guys again, they had food and supplies and we feasted like never before. We asked them what happened and they said a storm kept them from flying into Tumlingtar and then when they got there, none of the porters wanted to go to Makalu Base Camp as it was thought to bring on bad luck to go into that area in the winter. By the time they finally flew into Tumlingtar and gathered up some porters to go in with them they were well over a week behind schedule, due to that they were triple staging each day (walking three days distance in one day) to get to Makalu Base Camp. They knew we would have run out of food long ago and were worried more than us about our situation. After having breakfast, we packed up and started our two week out to the Tumlingtar airport and then from there we flew to Kathmandu. It was a long and beautiful walk going through village after village, through the Arun Valley.

It was one of the more peaceful moments in my life.

It had been a long trip, two expeditions back to back in the middle of Nepal’s winter, both events were historic which was the frosting on the cake, and it was a good way to begin my climbing career in the Himalaya.

This year was my 39th year in the Himalaya, 20 years on expeditions and 19 years running heliski trips. As you might imagine, I have an endless supply of stories, which I plan to share with you from time to time…

In the meantime, stay happy and healthy… and remember, life is a gift and so when possible take chances and live your life to its fullest, you’ll never regret it.

All the best, Craig

Powered by Froala Editor